“There’s a level at which words are spirit and paper is skin. That’s the fascination of archives. There’s still a bodily trace.”

—Susan Howe, The Telepathy of Archives

An Infinite Archive

Andrea Lipps and Julie Pastor

“There’s a level at which words are spirit and paper is skin. That’s the fascination of archives. There’s still a bodily trace.”

—Susan Howe, The Telepathy of Archives

To visit Es Devlin’s archive is to experience a kind of magic. Housed in an unassuming storage space in rural Kent, the relics of her 28-year practice form a skyline of towering boxes and bins stuffed with drawings, scale models, sketchbooks, photographs, notes, and books. Against a wall, paintings lean like dominoes in rows twenty canvases deep.

Opening a box invites constant surprise. The sketchbooks are like sculptures, their pages collaged with gauzy fabrics, painted metal, colorful glass, and miniature cogs. Models present jewel-like visions of designs for theater, opera, stadium tours, and immersive installations—among them delicate trees, mirrored mazes, and a bloodied bathtub no bigger than a fingernail. Personal photo albums record her first travels abroad with the considered eye of someone memorizing a place rather than documenting it, with photographs arranged in bands of color, texture, and light.

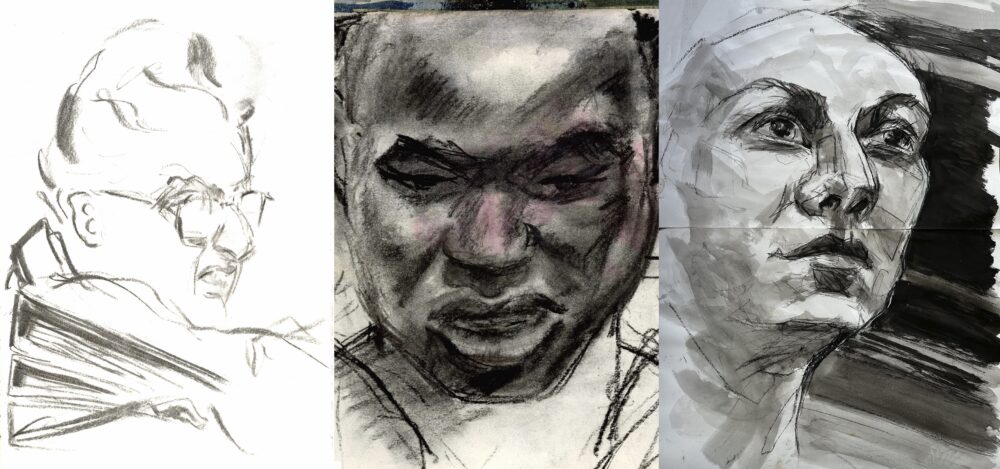

But it’s through her drawings that one most closely approaches her thoughts, whether through meditative portraits and studies or urgent concepts rushed across sheets of music, scraps of newspaper, printed emails, and set lists, or in the margins of scripts. She returns again and again to faces, figures, and hands, layering materials and paint to suggest more under the surface. Bodies are confined and contorted into tiny boxes. Faces burst beyond the edge of the canvas. The content, dynamism, and materiality are overflowing, suggesting a boundless creative mind.

Kneeling on the warehouse’s cement floor in early November 2022, we pored over her process. We’d come from New York to refine a list of objects to include in our exhibition at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. The depth, richness, and range of the work made choosing a challenge. We’d initially planned to spend a few days in the archive. We stayed for two weeks.

It is impossible to pin Es Devlin to a singular title, and perhaps it is defeating. She is polymathic. She is a storyteller, an artist, a designer, a director, a poet, a visionary, perhaps even an alchemist, whose work razes through disciplinary boundaries. Her canvas is temporary space, her materials are as intangible as her work is ephemeral: breath, light, music, time, and anticipation. Her additive practice reveals a limitless curiosity. To be in her presence is to be transfixed with creative energy, poetry, and a proliferation of ideas. She poses incisive questions of collaborators and immerses herself within texts. The result is the precise distillation of narrative in form: a merging of geometry, materials, and words into an armature that holds the ritual of performance. And yet, as she points out, “I do all this work and nothing physical remains. What I’m really designing are mental structures, as opposed to physical ones. Memories are solid, and that’s what I’m trying to build.”

The exhibition and book present Es Devlin’s prolific career and point to the future of her practice. She is dedicating her craft as an experiential storyteller to elicit emotions from audiences, nudging us out of apathy and into action, to imagine our civilization’s future and to act toward it every day, making concrete what is currently abstract. She examines the role of an artist in the face of civilizational crises and the importance of shared experiences, with clarified purpose around animism, regeneration, inclusivity, and intention.

1995–2003

The connections of geometries, forms, ideas, and process that reverberate throughout Devlin’s practice emerge in her archive. From her earliest theater work beginning in 1995, there is a devotion to an intensely rigorous process and an instinctive ingenuity, evidenced by the sheer volume of the archive’s ever-expanding content—over 10,000 drawings, models, sketches, and paintings to date. The success of the work is held up by the mountain of research, ideas, and iterations beneath the surface.

A love and sophisticated understanding of literature grounds her forensic study of primary texts. Never one to think without a pencil, Devlin pores over scripts, jotting notes, sketching quick drawings to convey an idea, always working toward visual metaphor to unlock thought structures contained in the text. The process opens itself to a wide range of sources for each project: researching and reading, probing, and exploring with her collaborators. She interrogates a text, turning it on its side to reflect meaning that’s not just on the page, but underneath it, above it, or bent around its corner, as though refracting it through a prism to transform an audience’s perspective. Through diligent process, she identifies precise form. As theater director and collaborator Lyndsey Turner describes, Devlin’s mind is “both forensic and associative.”

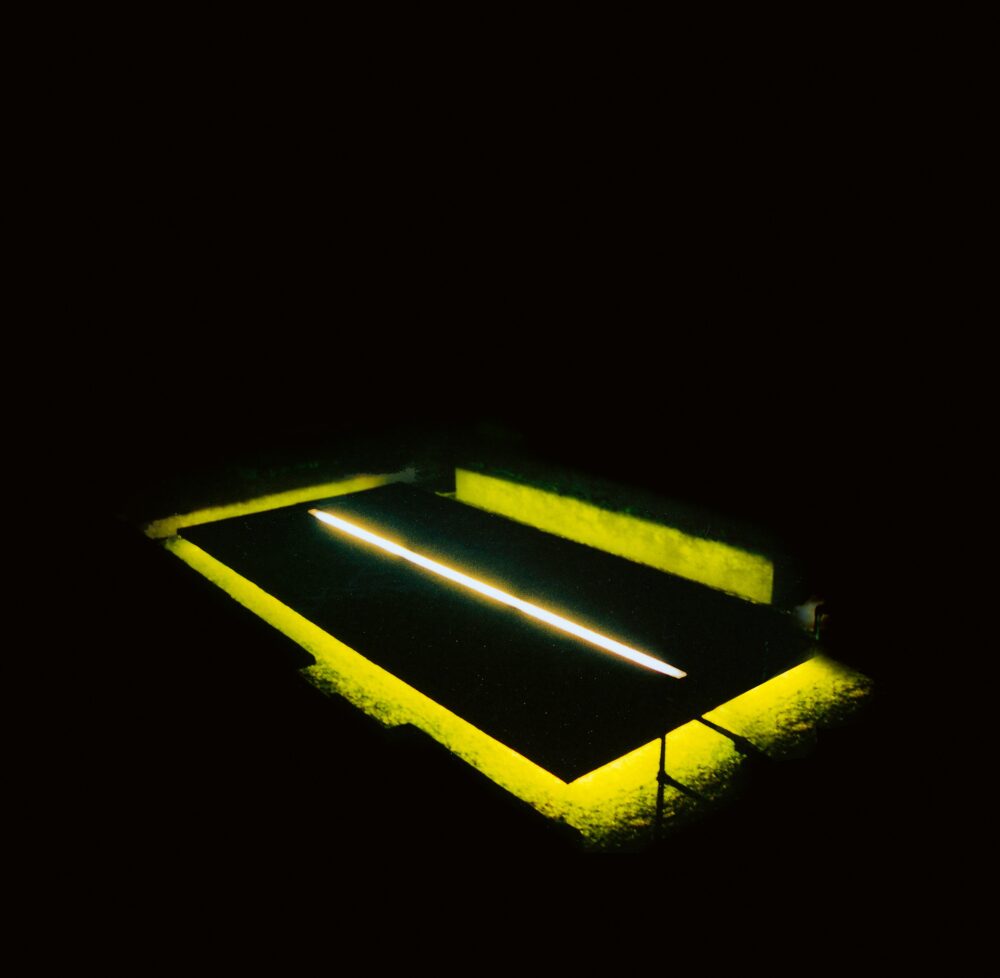

In her early proscenium-based work, we see her engaging light as material—reaching for light, revealing or masking it, using it in acts of transformation. The line of light in Howie the Rookie becomes the expanding horizon in Four Scenes, which is revisited in her staging of I Remember Red. Luminosity imbues the Betrayal set with memory. Kinetic blocks of brilliant, illuminated color emulate a modulating sequence of stained-glass windows in God’s Plenty .

Portraiture, long an interest from her early sketchbooks, begins to emerge as a central metaphor with the staging of Powder Her Face. The performance unfolds through an over-scaled wedding portrait of the play’s protagonist. Experimenting with the scale and framing of faces, Devlin draws on representation to suggest intimacy, a strategy she will apply across expanding terrains. As soon as she demonstrates an unrestrained instinct for world-building within theater, she extends beyond the proscenium.

2003–2016

In 2003, she began penetrating new fields when music, which had consumed her early sketchbooks, entered her professional practice. That year, she collaborated with director Keith Warner on Ernest Bloch’s Macbeth, her first European opera house production, in which a rotating perspective box delivered the play’s illusions. Saturated red paintings of arterial systems, early explorations for Macbeth, mark a fascination to which she returns in later work. That same year, Alex Poots and Paul Smith invited Devlin to design the set for post-punk band Wire’s farewell tour. The minimal staging and attendant projections—four cubes, each containing a band member and overlaid with projections of an eye, ear, mouth, or nose—not only signal the cube as a talisman in her practice but also present an abstracted portrait of a band in disarray. If her early stages had functioned as multi-layered narratives, they now began acting as instruments—every aspect serving sight, story, and sound.

The design for Wire attracted the interest of Kanye West, beginning several years of collaboration and launching Devlin onto bigger stages with ever-larger audiences and additional artist collaborators, including U2, Adele, Beyoncé, The Weeknd, and Dr. Dre and Kendrick Lamar, among others. As the scale of performances increased, so did the degree of audience anticipation, which she molded as a material. On stadium stages, she envisioned worlds in which performers became almost mythological—conduits to the multiple meanings fans ascribe to their songs. Portraiture became an often essential tool for calibrating energy within a stadium. Multistory sculptures project an artist as larger than life. Beyoncé emerges from a seven-story monolith on which her monumental image is projected; Miley Cyrus slides down a bright pink tongue protruding from the mouth of her over-scaled head. Within these environments, performers often appear surprisingly vulnerable, offering at once a sense of spectacle and intimacy.

Narrative remains essential. Kinetic, layered environments tell the stories behind musicians’ songs. Lyrics form fantastical or meditative landscapes. Crowds journey through concerts on a series of cresting and breaking waves. While arena tours can comprise an epic, the stages for televised performances present condensed, shorter stories. Devlin’s designs for the BRITs and MTV present engaging visuals that function on both stage and screen—a constraint she explored in greater depth in her designs for Olympic ceremonies in London and Rio. If the proscenium arch restricts an audience’s view, forcing the eye to a fixed vantage point, she masterfully focuses audience attention on monumental platforms, conceiving large-scale sculptures and activating light and color such that the stage begins to dematerialize.

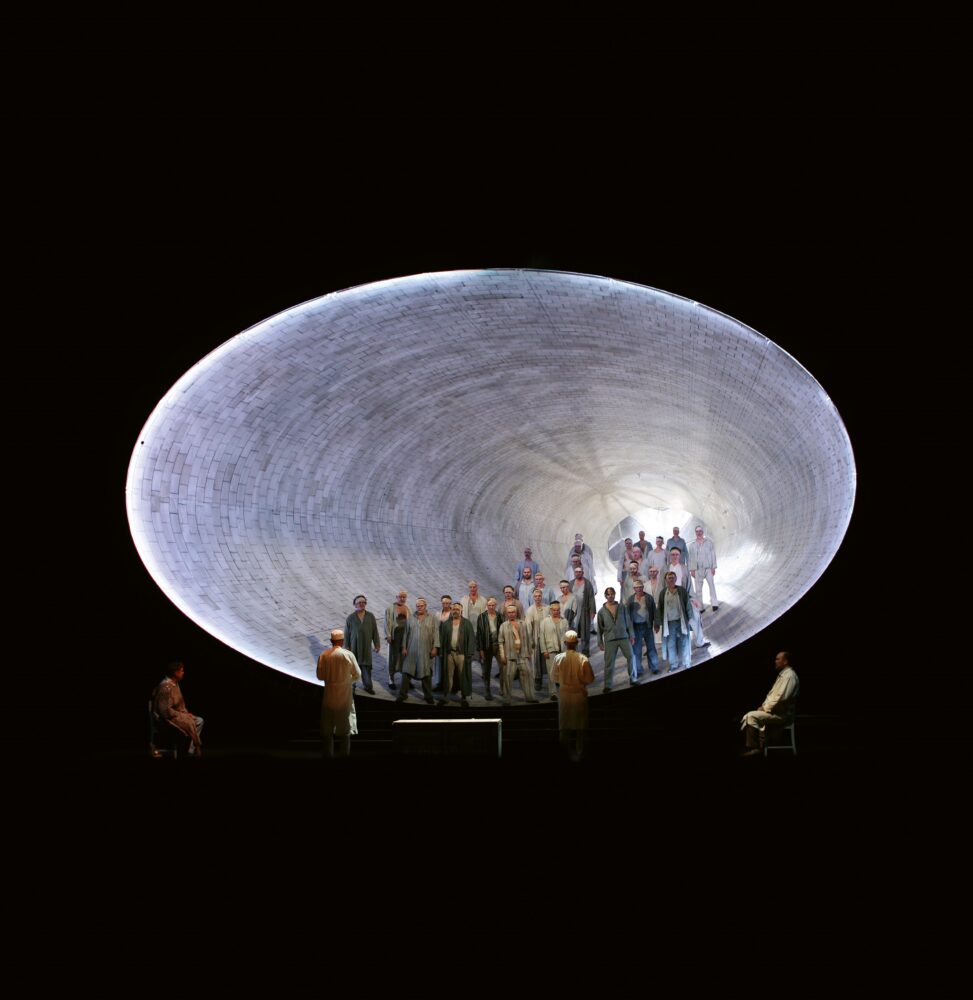

While a pop show tends to emphasize an individual, opera hinges on the power of collective voices. For Devlin, choral instruments often derive from a simple gesture or metaphor—Carmen throwing the cards that foretell her fate or Parsifal’s quest for compassion as a game of chess. Through rigorous readings of texts and iterative process, she distills complex stories into simple forms. Circles and ellipses enter her lexicon. A metaphorical landscape prioritizes the psychological story, and she deploys kinetic techniques in a continuous rhythm to propel a performance. Objects rotate, revealing and concealing scenes. Dynamic projection-mapping creates movement within stillness, carefully timed to the beats and needs of the action. And the objects amplify music, projecting the voices of performers or arranging them in stacked staves—a form that reappears in later work for Louis Vuitton.

Through her many collaborations, Devlin erodes and tears apart the seams between disciplines. The story of a song is equal to that of a play or a fashion collection or an opera. The more she experiments, the more she merges art forms to foster new modes of transformative performance.

2016–present

In 2016, Devlin began molding her craft to create ritual environments and performances around her own texts. Mirror Maze, her first large-scale installation, was a decisive work in which she eschewed the stage altogether. For the first time, she invited audiences to become the work’s protagonists. Audiences stepped through a hole in the work’s introductory film to become immersed in a mirrored labyrinth. This transformation of audience—from passive observers to fully embodied, active participants—marks a profound shift in the practice.

That same year, she was invited by Hans Ulrich Obrist to participate as a speaker in the Serpentine’s annual Marathon in London. Devlin used the opportunity to not just give a talk, but to create a work while on stage, making a performance of her process. Collectively, these works and the collaborations around them mark the beginning of her installation-based art practice. As she dematerializes the stage, action and audience coalesce in her art.

Like so many of us, Devlin has grown increasingly concerned, particularly in the last decade, about the climate and civilizational crises we face. The urgency to shift towards regenerative and harmonious ways of living with one another and the planet only continues to come into fuller relief with each IPCC report, extreme weather event, social justice movement, and mass migration. Her attention centers on texts of eco-philosophy and economic transformation that will sustain a flourishing world. If humans currently confront climate facts with stasis, then perhaps it is through art and imagination that new perspectives will take root. Art provides a forum to synchronize collective thinking. It is here that form and purpose meet in the trajectory of the work, unifying her practice.

With each commission, she dedicates her craft in service of narratives that will spark a shift in audiences: inviting contributions to collective poetry; mapping locations of historical cognitive shifts; bathing conference delegates in a forest of trees; kindling awareness of underlying patterns in human and non-human arterial systems; illuminating the beauty of linguistic diversity; and celebrating endangered species. Devlin often works with a quotational practice, collaging together extracts from devoured books to foreground these salient narratives, which she presents in immersive, sonic, and spatial environments that are rigorously researched and realized.

Perhaps the best way to define Es Devlin is as a composer of space and narrative, a sculptor of time and engagement. She wields spectacle, scale, and anticipation with an analytic and associative mind to extrude meaning and ritual. Her installation-based works invite all of us to participate and consider our connection to one another and to the planet, evoking emotions and advancing action towards our collective future. Her fearlessness in the face of boundaries releases her into a boundless practice.

The poet Susan Howe suggests an archive is an “empty theater where a thought may surprise itself at the instant of seeing.” Each object awaits a potential audience. Each drawing, text, model, or sketch reverberates with underlying meaning. The encounter surfaces the spontaneity and frisson of live performance. Intimate discoveries bend the arc of time when uncovering the inception of an idea, as evoked by the hand that pressed graphite on paper, leaving its bodily trace.

In our intimate experience encountering Devlin’s archive, we uncovered connections, threads, stories, and breadth in not just a body of work, but in a life. One can imagine each project and period forming a mental architecture that she temporarily inhabits; the archive, with its towering boxes, is a memory palace where they all simultaneously coexist, much like the book and exhibition.

What began as an initial sketch found in a box became a detailed rendering made with a community of collaborators, and finally manifested in a form experienced by thousands or hundreds of thousands. It’s the expansion from the individual, with just a sheet of paper and pencil, out into the creative community, the audience, and beyond. For Es Devlin, this is breath, this is life. It begins with one and leads to the infinite.

Es Devlin, Studies, Archive Unboxed installation, "An Atlas of Es Devlin," 2023

Courtesy of Es Devlin

Production photograph, Howie the Rookie. By Mark O’Rowe, staged 1999, Bush Theatre, London, UK

Courtesy of Es Devlin

Es Devlin, Study, Four Scenes, Mixed media on photographic print. Staged 1998, Sadler’s Wells, London, UK

Courtesy of Es Devlin

Es Devlin, Study, Flag: Burning. Mixed media on paper. Staged 2003, Wire Farewell Performance, Barbican Hall, London, UK

Courtesy of Es Devlin

Production photograph, Parsifal. By Richard Wagner, staged 2012, Royal Danish Opera, Copenhagen, Denmark

Courtesy of Es Devlin

Installation photographs, Mirror Maze. Installed 2016, Copeland Park, Peckham, London, UK

Courtesy of Es Devlin

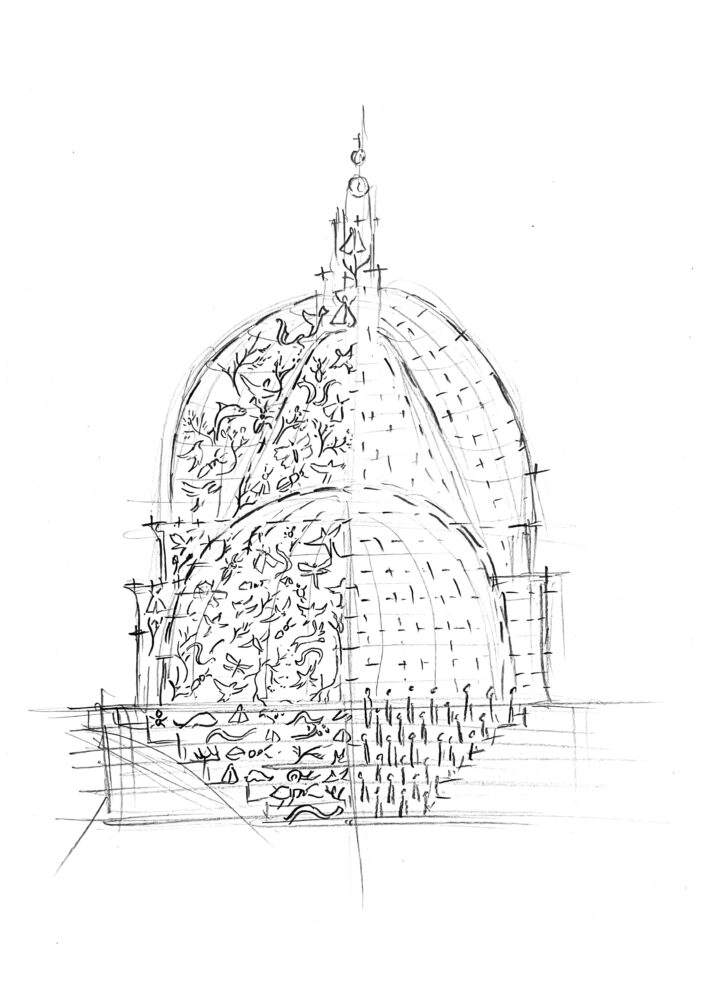

Es Devlin, Study, Come Home Again. Graphite on paper. Installed 2022, Tate Modern lawn, London, UK

Courtesy of Es Devlin

British artist and designer Es Devlin (born 1971) is globally renowned for her large-scale installations and sculptures for performances. In this digital platform, you will encounter studies and models paired with short texts from Devlin that describe her process of making them. Choose a topic to explore early pieces in Devlin’s archive, her small-scale studies , or the way in which she engages with forms, portraiture, and participation in her work.

An Infinite Archive

Studio

Iris

Archive Unboxed

Sculptures, Ideas to Forms

Studies, Abel’s Mask

Studies, After Hours Til Dawn

Studies, Bangerz

Studies, Come Home Again

Studies, Electric

Studies, Experience + Innocence

Studies, Flag: Burning

Studies, Forest of Us

Studies, Fundamental

Studies, Hello

Studies, Innocence + Experience

Studies, Legend of the Fall

Studies, Memory Palace

Studies, Mirror Maze

Studies, PoemPortraits

Studies, Sphere

Studies, Unknown Soldier

Studies, Witness

Study, Die Tote Stadt

Study, Don Giovanni

Study, Free Your Mind

Model, Atlas

Model, Betrayal

Model, Don Giovanni

Model, Fundamental

Model, Howie the Rookie

Model, La Caja Mágica / The Seed

Model, Legend of the Fall

Model, Macbeth

Model, Parsifal

Model, The Hunt

Model, The Lehman Trilogy

Sculpture, Songs for Sorrow

Model, Abel’s Mask

Model, Bangerz

Model, Carmen

Model, Chimerica

Model, Compton Super Bowl

Model, Flag: Burning

Model, Hello

Model, Innocence + Experience

Model, Les Troyens

Model, Progress

Model, London Olympics

Study, Dynamic Cube

Study, Perforated Screen

Model, Come Home Again

Model, Five Echoes

Model, Forest of Us

Model, Infinite Library

Model, Memory Palace

Model, Mirror Maze

Model, Please Feed the Lions

Model, Poem Pavilion

Model, Redraw the Edges of Your Self

Model, Room 2022

Model, Your Voices

Model, Zoetrope

Theater in a Box

Films

Book Unbound