This fairly deserted and dicey neighborhood, newly labeled “Tribeca” (the Triangle Below Canal Street), had originally been the dairy and spice district in Manhattan until these businesses began to flee the city for cheaper rents across the Hudson River in New Jersey, and it became a ghost town. Downtown was cheap and filled with artists. Recognizing that artists have often been unintentional gentrifiers, city officials ingeniously saw the opportunity and began offering huge tax incentives to certified working artists if they purchased any of these Tribeca buildings (which were for sale at very low prices), on the condition that they would move into and convert them into residential lofts. Luring artists to inhabit this deserted neighborhood inevitably gentrified it, and real estate prices rose, eventually bringing in coveted tax revenue to the city.

I took the bait. My Lispenard Street loft cost me only $16,000 and had been a vitamin factory. The building was a mess, but soon the other lofts in my building began selling to all sorts of different creatives, and we began cleaning it up. Upstairs, the artist Daniel Buren moved in, and the lighting designer Ingo Maurer moved in next door to him. I had a day job working at the SoHo News as style editor to pay the mortgage while trying to figure out how to make a living and do my art without getting a stupid job that would suck the life out of me. Our building was a small DIY co-op where everyone knew everyone. I was asked to be on the “board,” so reluctantly I became the treasurer, responsible for collecting the monthly maintenance checks ($300 a month!) and depositing them in a local bank.

One day I heard from a neighbor that a well-known fashion designer named Willi Smith had bought the loft downstairs from me. I was excited because I knew and loved Willi’s work and was dying to meet him. It turned out he was a fan of the crazy style pieces I was doing at the SoHo News too, so we hit it off right away. Willi was definitely not an underground fellow, and moving into this funky, downscale factory building was a radical and unpredictable leap for someone as successful as he was at the time. It said a lot about him that he bucked upscale lifestyle expectations, choosing instead to live in an unconventional, gritty neighborhood surrounded by artists. To me, it seemed weird that someone so successful would want to live in this raw building on our rat-infested street.

I was a rebellious underground artist in those days, and Willi was the very first true celebrity I’d ever met. He was a press darling, always interviewed on the morning shows and written about in the New York Times and Women’s Wear Daily. He was also Black and gay, beloved by the media and fashion community, and a huge icon and hero to African Americans everywhere. His signature label, WilliWear, was immediately recognizable, and although the clothes were made for the everyday, they were truly unique. Willi seemed to sense innately what the new, diversifying masses in America really wanted to wear on the street. In retrospect, I can see that Willi Smith invented “streetwear.” His oversized, fun sportswear was accessible, democratic, and very affordable. And boy did it sell, flying off the racks in department stores like Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s.

When Willi moved into our building, he brought something new to the neighborhood. I would laugh every morning on my way to work when I’d see Willi’s big, long, black, fancy limousine and driver, George, waiting outside next to all the dirty garbage cans to take him up to the Garment District to his office. Willi was the first person I ever knew with a limousine, and he would sometimes give me rides in it. One day, for my mom’s birthday, he loaned me George and his limo, and my mom was beside herself when we drove around the city sipping champagne in the back.

Willi kept getting more famous. Whenever I would deposit our building’s maintenance checks at the Citibank on the corner every month, the bank tellers behind the counter, mostly women of color, would gather around me to ogle Willi’s check that was among the others. They were starstruck and would grill me: “What is he like?” “Is he as nice as he seems?” “I saw him once on Canal Street, and he smiled at me.” “Look, I’m wearing his blouse!” “Tell him we love him!”

This admiration for the designer was not just in New York City. Willi’s clothes were sold everywhere, and he was famous all across America. He traveled the country doing personal appearances and would be mobbed for autographs like a rock star. He was not a snob and was someone everybody, no matter what ethnicity or income bracket, could relate to. He was an uncontroversial guy—not too gay, not too hip, not too famous to hug you. He was relatable and approachable, and so were his clothes. Willi could be your friend, your brother, your son, your uncle. He was beloved by millions of American women, including me.

Willi and I became fast friends. I began going to his fashion shows, dinner parties downstairs, meeting his friends, turning him onto mine, helping him navigate the neighborhood and the downtown underground art scene, while he would invite me to fancy events, whether dinner at Mr. Chow or openings at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where he would always be the first to see some sort of new, radical performance art or dance, whether Pina Bausch or Bill T. Jones. Willi brought me to his office often, and I was welcomed into the WilliWear family, especially by his amazing business partner and dear friend, Laurie Mallet, who was his greatest fan and supporter. Laurie made it all happen for Willi. She was the force behind Willi for sure.

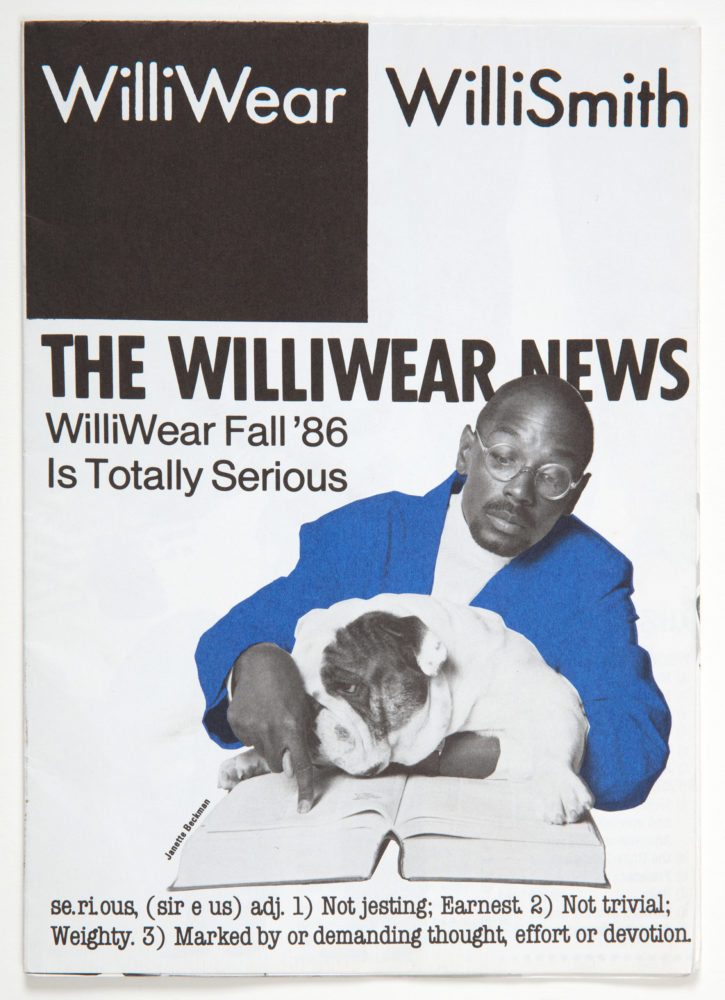

Around this time, the SoHo News closed suddenly, and I began plotting with some friends to start a new magazine covering downtown culture called Paper. I secretly showed Willi our prototype late one night at his loft. He went crazy when he saw it and said he wanted to show it to Laurie the next morning, and they would help me in any way they could. I didn’t know what I was doing, and Willi and Laurie had a big company with lawyers and infrastructure, so they began to advise me and help us launch in the most generous way. And of course, WilliWear advertised from day one in Paper. Laurie was not just a super-smart businesswoman; she was also an avid art lover, collector, and unflagging creativity supporter who really inspired and influenced Willi in this area. She adored artists of any type, whether painters, sculptors, architects, performers, or, even in my case, an underground DIY zine maker. WilliWear was a midpriced mass sportswear company, but it was special because Laurie made sure that WilliWear DNA was fueled by art and creative collaborations. Willi and Laurie loved Paper and invited me to create something called the WilliWear News, a foldout poster that looked like and was produced by Paper, but was all about Willi. WilliWear collaborated with many artists, including Christo, choreographers Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, the film director Max Vadukul, and even the architectural collective SITE, which designed the WilliWear headquarters, transforming it into a piece of art—a gray monolith abstraction of “city streets” complete with cinderblocks, chain-link fences, and concrete floors. This was 1983, and it was totally unheard of for a company to integrate art so heavily into their brand. Willi’s shows, held in their SITE-designed showroom, were never traditional. His casting was diverse and amazing thanks to his best friend, who later became a dear friend of mine, a beautiful force of nature named Bethann Hardison, who founded a unique modeling agency at the time.

Soon AIDS began taking an enormous toll on our creative community downtown. It also began to devastate the fashion world. We all lived in a state of shock and fear, with friends dying all around us every day. I’d see Willi in the elevator on my way to work for years, and I could sense that he wasn’t well, but we never spoke about it. AIDS was like that in those days. And when someone afflicted was a celebrity, it carried an extra burden of shame and denial. It all happened so fast. Suddenly, one day my friend and neighbor Willi, the shining star, was gone. The loss was so devastating and confusing. We were all so young.

Over the past three decades since Willi’s death, I watched an enormous multibillion-dollar streetwear trend gain a grip on America. I always knew where this came from. Streetwear never really existed until Willi invented it. I often wonder what Willi would think of it all if he were still around. I know he would have loved what Pharrell has done with clothes, but what would he think of Yeezy or Virgil Abloh? Or Supreme? For sure, Willi would have designed Barack Obama’s inaugural suit. Willi Smith was important and deserves an important place in the history of US fashion. He was intuitively prescient and manifested a groundbreaking and diverse look to be worn on the street by everyone everywhere. History is the proof of what a visionary he turned out to be.