Willi Smith Street Couture

The Willi Smith: Street Couture Virtual Exhibition illuminates how American designer Willi Smith (1948-1987) and his collaborators broke down social, cultural and economic boundaries by marrying affordable, adaptable “street couture” with avant-garde performance, film and design.

Your journey so far

All pages

Alvin Bell

Artist T-Shirt by Dondi White

Artventure

Attitudes

Audrey Smaltz

Beginnings and Career

Bethann Hardison

Bethann Hardison Oral History

Bonnie Brownfield

Brian Howard

Cesar Moreno

Christa D’Souza

Christine Rucci

City Island

Elyn Rosenthal

Jeff Tweedy

Jeffrey Banks

Jon Haggins

Joseph Delate

Juan-Manuel Alonso

Kelvin Garvanne

Knowledge through the Hand

Laurie Mallet

Laurie Mallet Oral History

Map Print Skirt

Mark Bozek

Martha Nutt

Menswear Illustrations

Mindy Grossman

Miralda’s Dressing Tables

Pat Cleveland

Patterns for You

Peter Goldfarb

Prudence Harvey

Reba Ford-Sams

Shailah Edmonds

Sightseeing

Spring 1979 WilliWear Presentation

Stephen Burrows

Stuart Lazar

Style over Status

The Greatest Showman

To Be American

Tsia Carson

Uniform Shirt and Pants, The Pont Neuf Wrapped

Veronica Jones

Vijay Agarwal

Wedding Dress for the Black Fashion Museum

Williwear to Streetwear

Southern Voice—February 15, 1990

About Willi Smith

Alvin Bell

Anthony Barboza

Artist T-Shirts and Prints

Audrey Smaltz

Bethann Hardison

Bill T. Jones Oral History

Bonnie Brownfield

Brian Howard

Carla Moore

Cesar Moreno

Cheryl Braunstein

Christa D’Souza

Christine Rucci

Christopher Andrews

Cynthia Stubbs-Hill

Diane Meier

Edwin Schlossberg

Elyn Rosenthal

Fern Mallis

Forest Young

Groom’s Suit

Ian Hylton

Iris Simpson

Jack Travis

Jackie Sanchez

Janette Beckman

Jeff Tweedy

Jeffrey Banks

Jon Haggins

Jorge Socarras

Joseph Delate

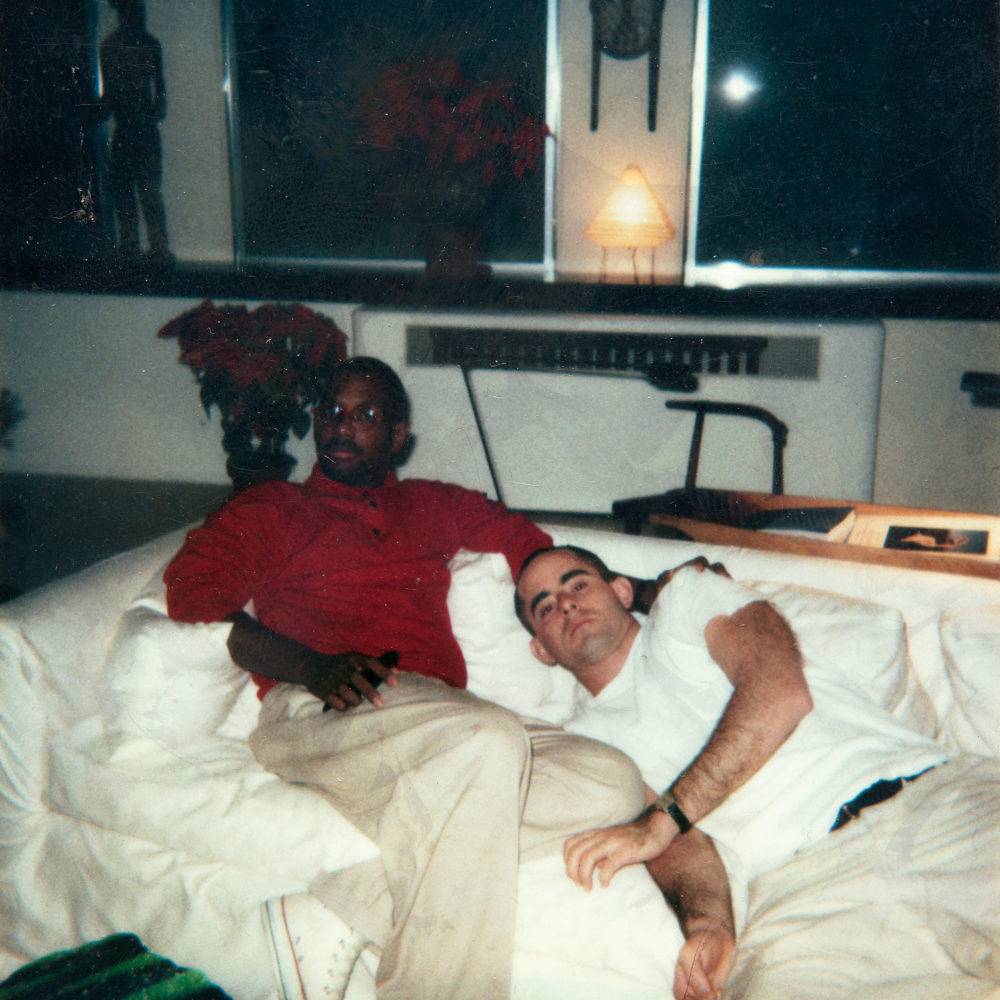

Just (Some) Friends

Kelvin Garvanne

Kim Hastreiter

Kim Steele

Laurie Mallet

Les Levine

Linda Mason

Loren Harrison

Lynne Tillman

Mark Bozek

Martha Nutt

Mary Jane Marcasiano

Max Vadukul

Mindy Grossman

Om Batheja

Pat Cleveland

Patrick Patterson

Paul Tschinkel

Penny Payne

Peter Goldfarb

Peter Gordon

Peter McQuaid

Prudence Harvey

Reba Ford-Sams

Sabrina Lahiri

Sarah Khan

Shailah Edmonds

Stacey Appel

Stephen Burrows

Stuart Lazar

Sylvia Waters

Todd Siler

Tom Healy

Tsia Carson

Vernaculars of Black and Queer Remembering

Veronica Jones

Veronica Webb

Vicente Wolf

Vijay Agarwal

Wendy Goodman

Willi Smith and Friends Poolside, 1976

Willi Smith: On the Record

Willi Smith: Swervin’ in the Kingdom of Dreams

Willi Smith’s Glasses

X Baczewska

Secret Pastures

Secret Pastures Collaborator Portrait

Take-Off from a Forced Landing

A Closer Look at Secret Pastures

Bill T. Jones on Secret Pastures

Bill T. Jones Oral History

Costume Illustration for Cotton Club Gala

Costumes for Take-Off from a Forced Landing

Diane Meier

Feast or Fashion

Illustrations and Costumes for Deep South Suite

Jorge Socarras

Linda Mason

Peter Gordon

Publicity Photograph of Bernadine Jennings and Leon Von Brown

Real Clothes for Real Dance

Expedition

Expedition Detail Image

Expedition Film Screening Ticket

Expedition Press Kit and Invitation

Expedition Screening at Ziegfeld Theatre

Future Crossings

Les Levine

Max Vadukul

On Set of Expedition

Paul Tschinkel

Penny Payne

Ruth E. Carter on School Daze

WilliView Maquette

Bill Bonnell for WilliWear

Dan Friedman for WilliWear

Design for Willi Smith

Fern Mallis

Jack Travis

Kim Hastreiter

Loft on Lispenard Street

Polydisciplinary Magnetism

Poster, WilliWear Fifth Avenue Store

Rebellion in Design: Developing a Blueprint for the Future

SITE Drawings

SITE’s Iconic Ghost Cityscape

Vicente Wolf

Willi Smith In Pieces

WilliWear Map Print

WilliWear New Wave Graphics

WilliWear Showroom