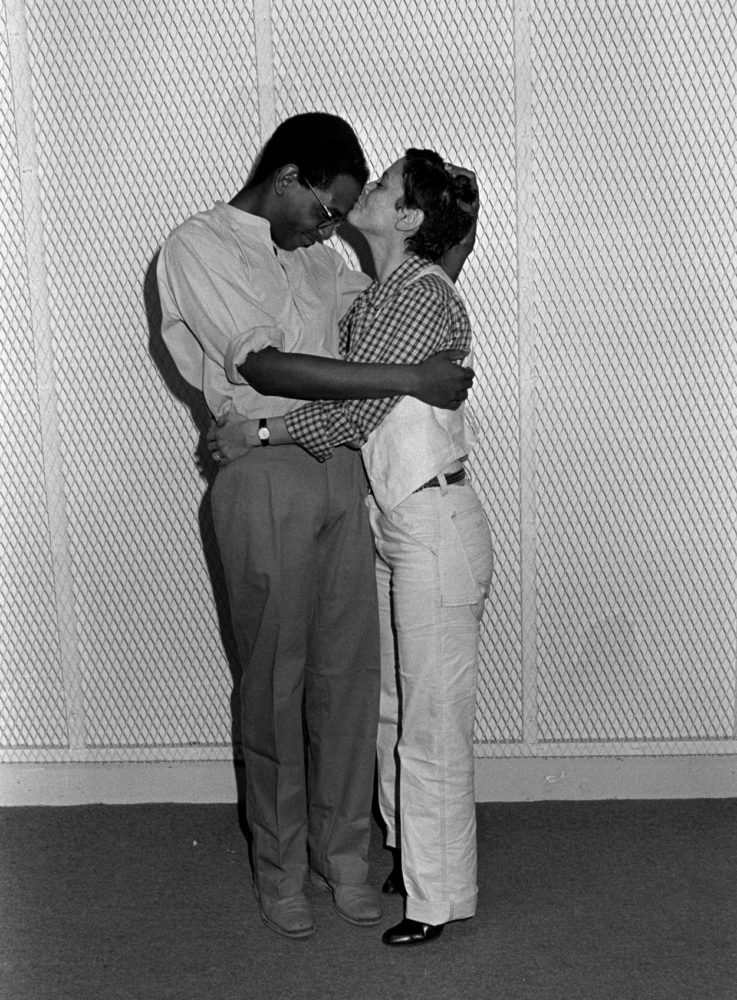

My mother’s business was in fashion. She worked as a consultant for large corporations developing trends, creating markets, and instigating collaborations between different industries. My stepfather Severo is an artist, an abstract painter. Both my mother’s work and Severo’s, design, art, and industry were part of my education very early on. In 1973, I traveled to New York on holiday and took a portfolio of fabric designs done by French artists, thinking I could sell them to American fabric manufacturers at a higher price than what they were getting in Europe. I did manage to sell a few and paid for my trip. It was through this business effort that I met Willi Smith. It was love at first sight. When he came to Paris for a business trip he called me.

When I went back to New York to follow my then boyfriend, who was going to study for an MBA at Columbia University for a couple of years, I called Willi. I was at that time rather conventional socially. When I met Willi, I was immediately in awe of him: handsome, funny, extraordinarily stylish, not fitting any of my social classical criteria. He asked me to become his assistant at Digits and I entered into a new world.

My first experience in fashion in America included focusing on fabric choices, cuts of garments; devouring the fashion magazines to make sure we were in the know; meeting journalists, designers, artists; and going to really great parties. I became part of Willi’s life, discovering New York in the seventies, from loft living to the art world. Then the business we both worked for went bankrupt. I went to work for another company, Ellen Tracy. Willi started his own business with his sister, Toukie, and his friend Harrison Rivera-Terreaux.

I found my entrepreneurial calling when an Indian industrialist came to see me at Ellen Tracy, trying to sell them the possibility of manufacturing in India. They did not buy it, but I did. With the encouragement of my boyfriend, I took all of our savings, $5,000 at that time, and went on a trip to India to manufacture a collection of shirts. I had never been to India before. My host was charming and welcoming, but I realized soon that he knew more about plastics (his family’s business) than garment manufacturing. We did not really know how to source fabrics, get samples made. He approached one of his friends, Vijay Agarwal, who had started a very small factory in the industrial zone of Bombay. He agreed to make samples for us.

I got back to New York with my collection and tried to sell it to buyers from our loft in SoHo. I was not very successful. In the meantime, I was trying to figure out a business model, using what I had felt to be the amazing potential of India as a source of manufacturing. At that time India was not known for quality manufacturing but for access to inexpensive labor and beautiful cotton fabrics. Actually, the market was inundated with Indian gauze shirts. But the demand kept increasing.

I called my Indian partner and asked him to source the fabrics and the manufacturing to meet the demand. He contacted Vijay, and it looked like we were in business. I placed my first order to India (using all the capital available and the help of my partner). It seemed that everything was on the right track. We forgot that none of us had been involved in manufacturing before, and when the first shipment arrived, it was a disaster: wrong color, wrong size assortment, buttons melting, white lining showing through in the collar, pencil marks everywhere.

Our first client was Macy’s. We selected by hand the best of the crop. I went every day to 34th Street to count the shirts and check whether any were selling. Not really. . . . Learning from our mistakes we put in place a rigorous quality-control process. At that time with a simple concept (one style in a multitude of colors), a good-quality manufacturing unit, and a great salesman, we were ready to take off, and we did. Every month we sold thousands of those shirts.

Most of the time I was alone in my office surrounded by boxes full of shirts. I started to get depressed. At the same time Willi’s business did not get any traction either, and he was worrying about his future. He did not want to go and work for one of those Seventh Avenue manufacturers. He came to visit me at my office and did not like my Frye boots and the boxes of shirts piled up. It was a scene.

This is where the inspiration came. I said to Willi, “I made a little money this year. I would love for you to come to India with me. I think you will be very inspired. I will pay for the trip, and we will bring back a collection. I will give you a royalty on everything we sell.” To my great surprise Willi said okay, and we started planning our trip. Willi had never been to India, and our arrival was a shock to him, not only the culture, which is so different, but also the rudimentary facilities in the factory compound.

When we arrived in Bombay, the airline had lost Willi’s suitcase, so for the first couple of days he was wearing shorts and cowboy boots (not a regular look in India where grown men only wear pants). Our Indian partners were quite amazed by Willi’s personality, and, after getting over the first surprises, they were under his charm.

Compared to everybody else, Willi knew a lot about garment making and was leading the way. We were lucky to be staying at the most fabulous hotel, the Taj, which made up for the various obstacles we were facing during the day. The factory had one patternmaker, who did not speak English, and most of the workers were men. Willi managed to establish a relationship with everybody, from the owners of the factory to the little hands. He communicated with the patternmaker with gestures. It was quite amazing. The factory was used to producing our shirts but had never produced a coat, pants, or a jacket. The workers were paid by the piece and did not enjoy (at least at the beginning) working on harder pieces. Some of them ran away. It was not easy to find zippers, so we used a lot of buttons instead.

The first time around we had to use fabrics from the market (plain poplin and a heavy cotton used for workers’ uniforms). After a few weeks of intense work, we managed to come back with a very small collection, more like a little grouping, a couple of jackets, a couple of shirts, skirts, and the pants. The star pants were the WilliWear fatigue pants, Willi’s fabulous interpretation of cargo pants. WilliWear was born. Instead of a royalty I gave Willi 20 percent of the business. We were officially partners. We organized a basic showroom in our offices. I bought a buyer’s guide and started calling stores from A to Z on both coasts. Willi was calling the press and people he might have known from his previous job. It was not easy.

We managed to get appointments with the fashion directors of major stores. Macy’s gave us a shot with a window on 34th Street. The first production arrived in our office a couple of months later, and it looked good. Women’s Wear Daily gave us some good reviews. Out of this first group one item started selling incredibly well, and other manufacturers copied it. They were calling it “the WilliWear pant.” The buyers came to check out the company. Mickey Drexler was at Abraham & Straus and gave us a good push. Then it was Saks and Bonwit Teller. The press started to support Willi in a great way. We were on a good track. We kept going to India to design the collections, and our relationship with the factory, the country, the culture was an important part of our success. We spent several months of the year there.

After the first couple of seasons we decided to do a fashion show. This is where we started our foray into the art world. We had our show at the Holly Solomon Gallery in SoHo. It was a big success. We were doing well, but started to feel some tensions as the concept of cotton in the winter was not obvious for the stores to accept. It was hard to be a one-season company. We developed our sourcing to be able to have some winter looks. Hong Kong became our winter product supplier.

Of course, many ups and downs followed, but WilliWear was a serious company. Willi was becoming a real star, and we were on a large cloud. The rest of the story is more well known, as there were quite a few articles written on this unlikely partnership between a French woman who might have become a diplomat, migrating to New York, and a fabulous young Black gay designer.