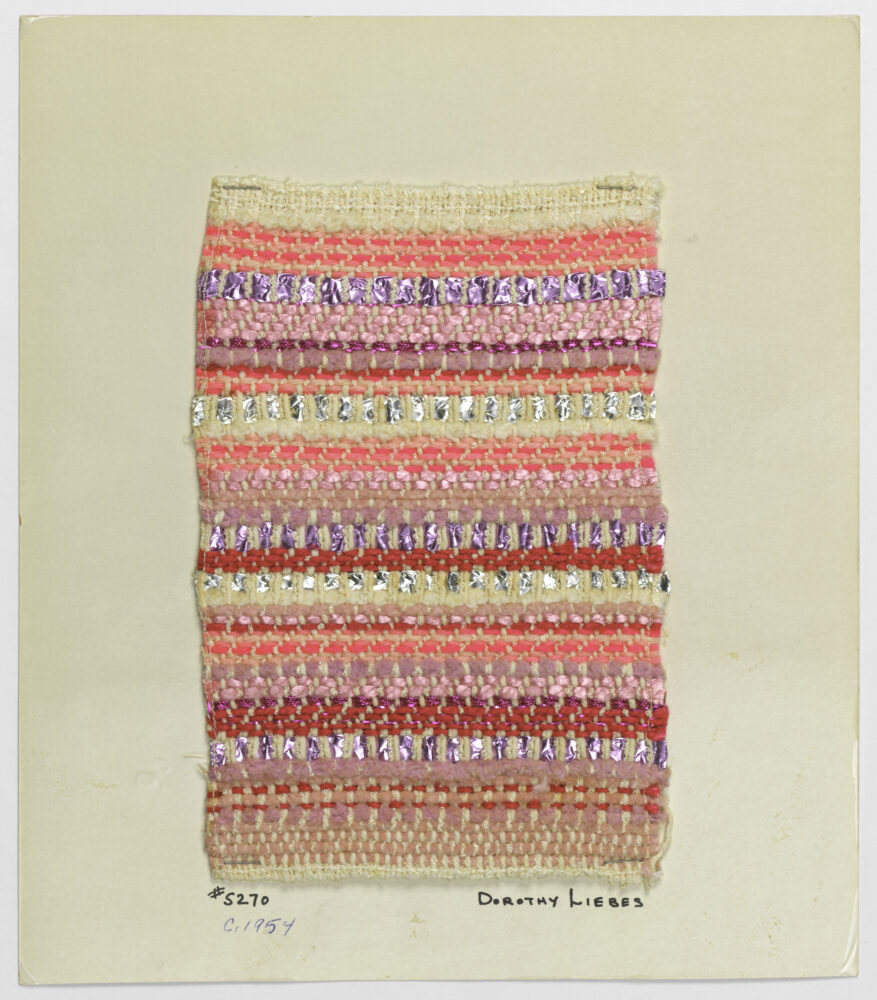

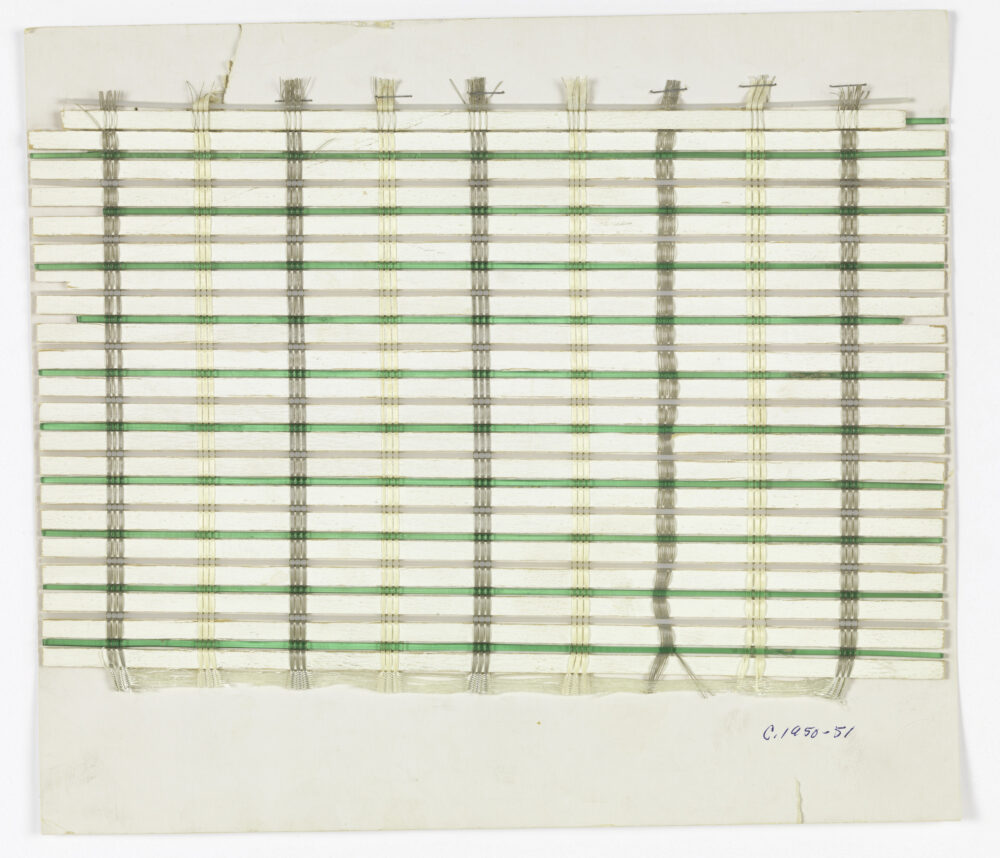

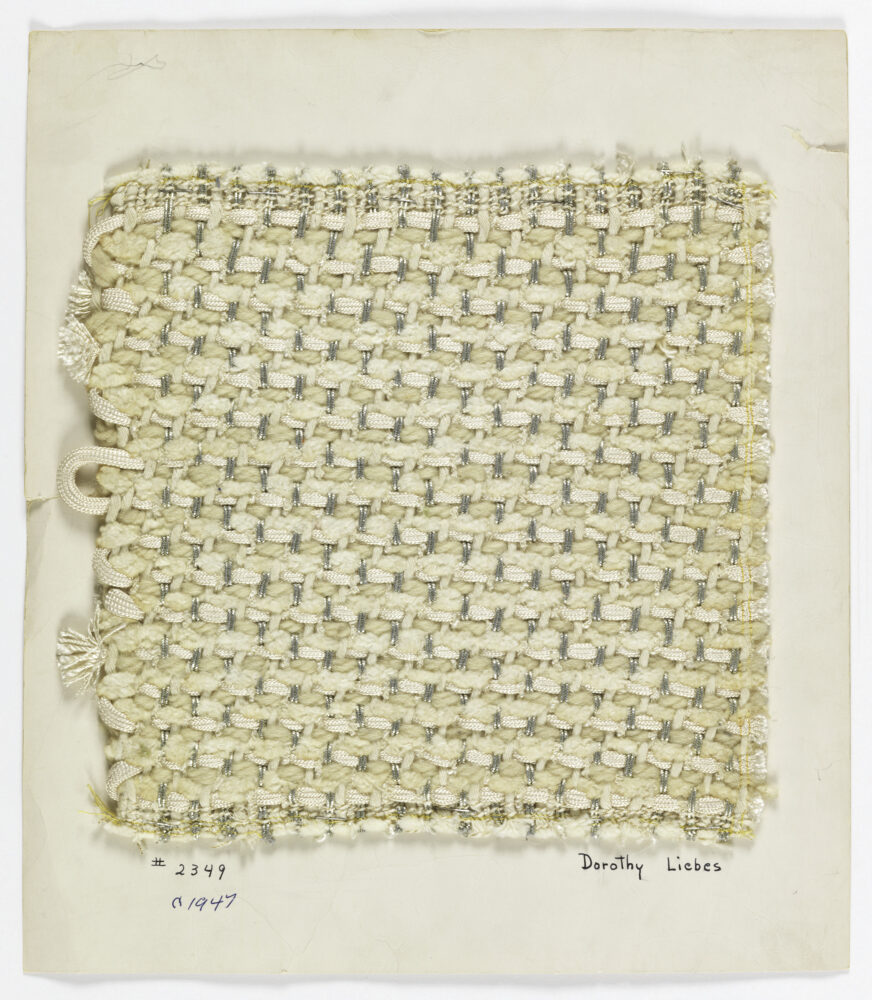

“For materials, I used everything I could lay between a warp: scraps of wool, yarn bought at the five-and-dime store, even Christmas ribbons. Out of necessity, I put materials on the looms not usually used in weaving.”

—Dorothy Liebes [1]

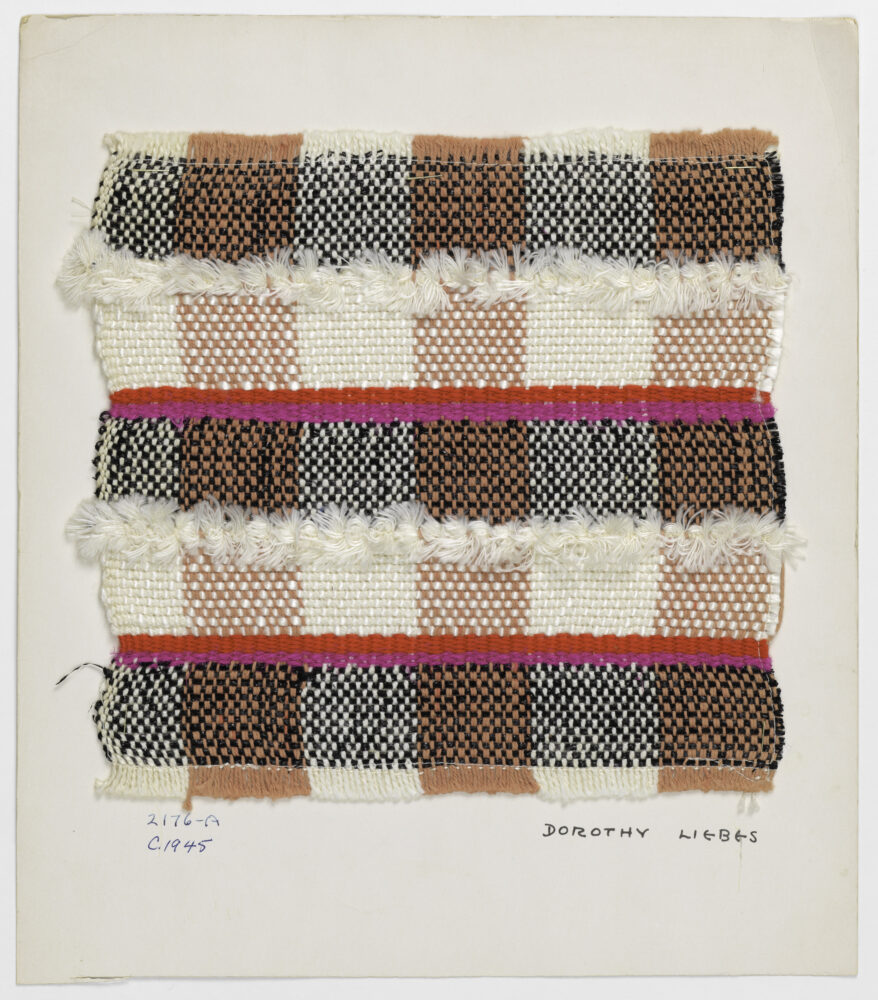

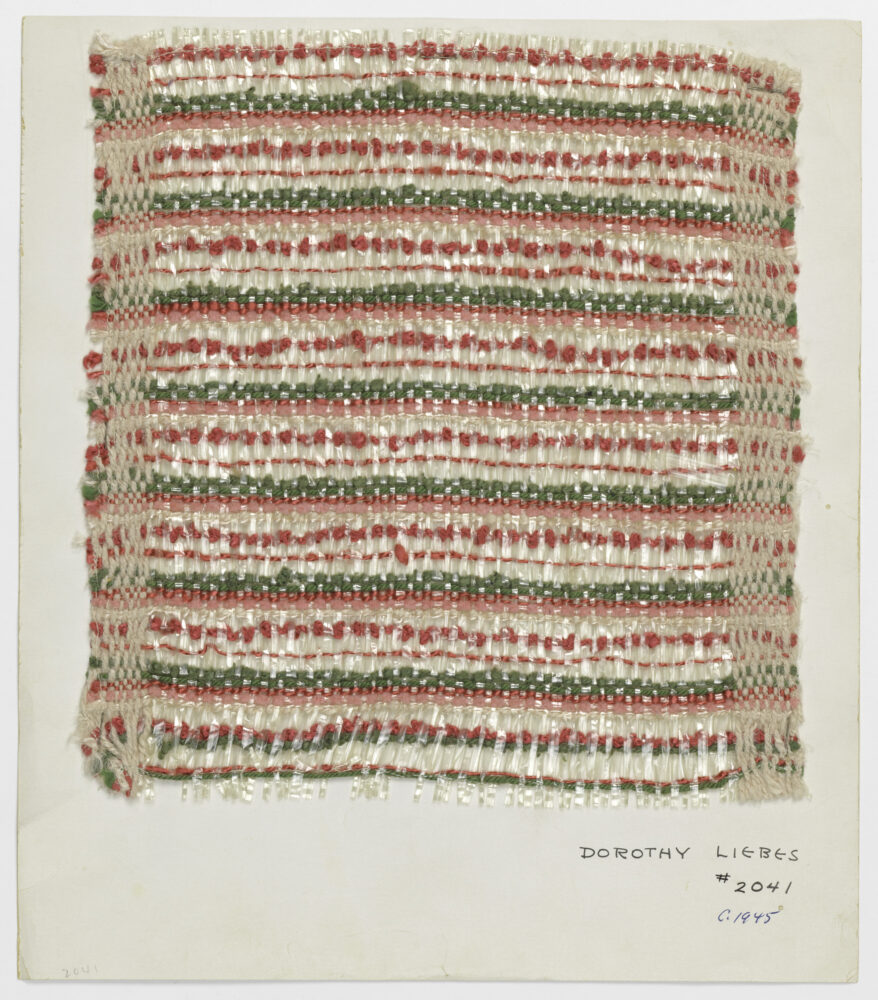

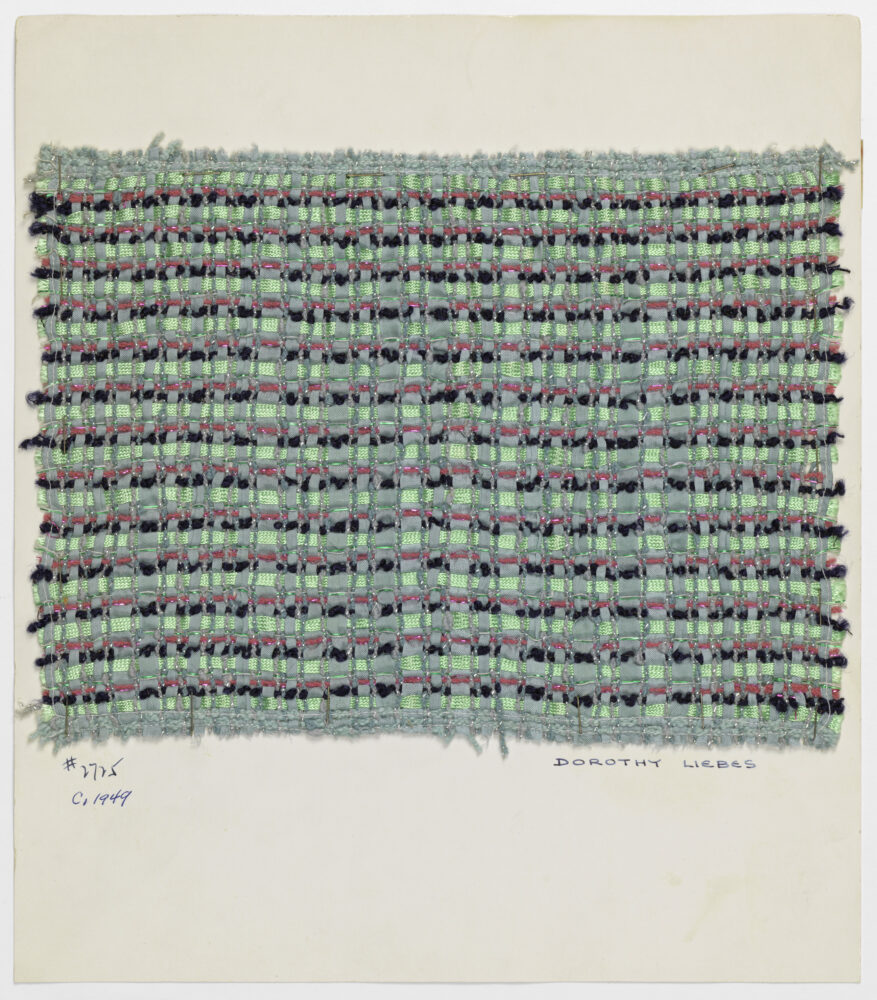

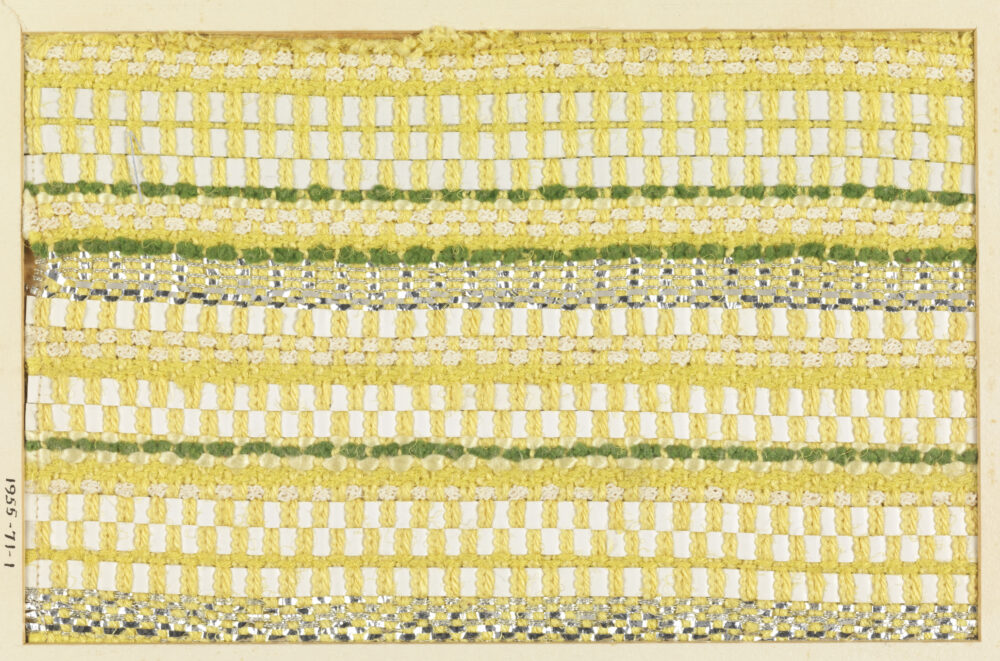

Materials—in scarcity or never-imagined abundance—steered the course of Dorothy Liebes’s career. She opened her first studio in 1930, during the Great Depression, shortly after leaving her first marriage with nothing but her clothes and her loom; she wove with inexpensive or found materials out of financial necessity. The onset of World War II brought restrictions on nonmilitary use of priority materials, including many textile fibers and dyes. Undeterred by the lack of wool and silk, Liebes experimented with mohair, rayon tow yarn, jute, vinylite, and other unusual materials, leading her own company and her industry partner, the Goodall company, successfully through the war years with her inventive blended fabrics.

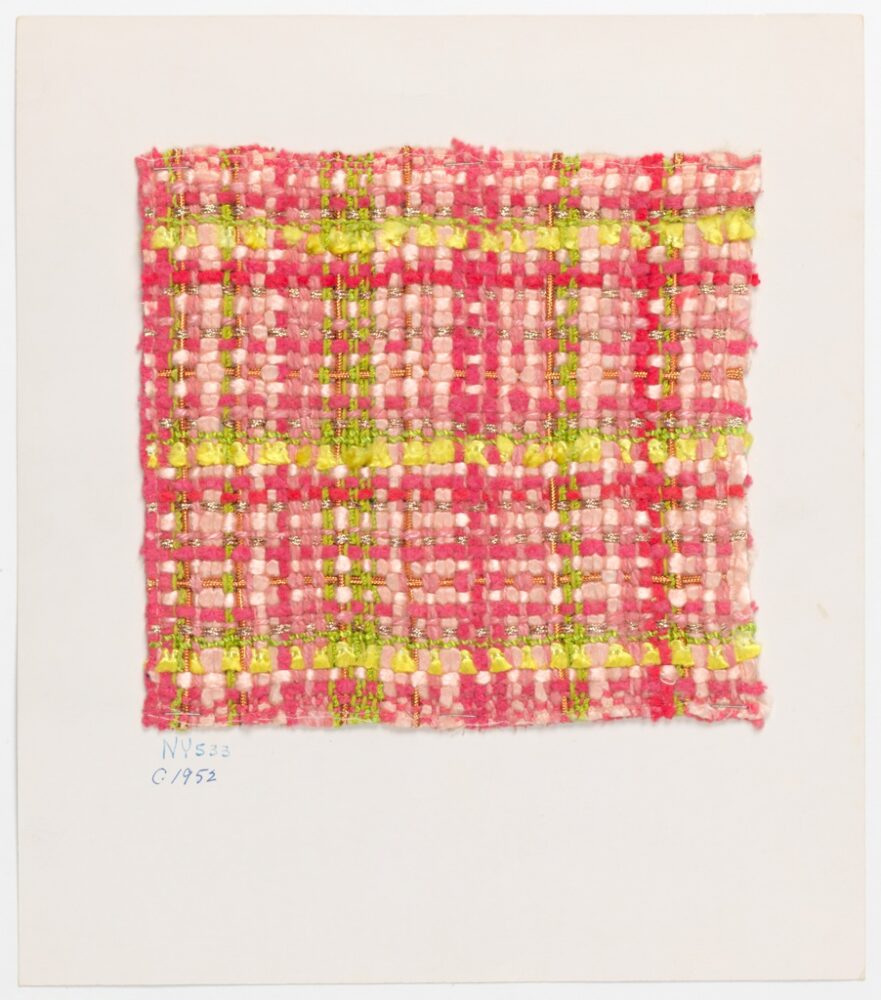

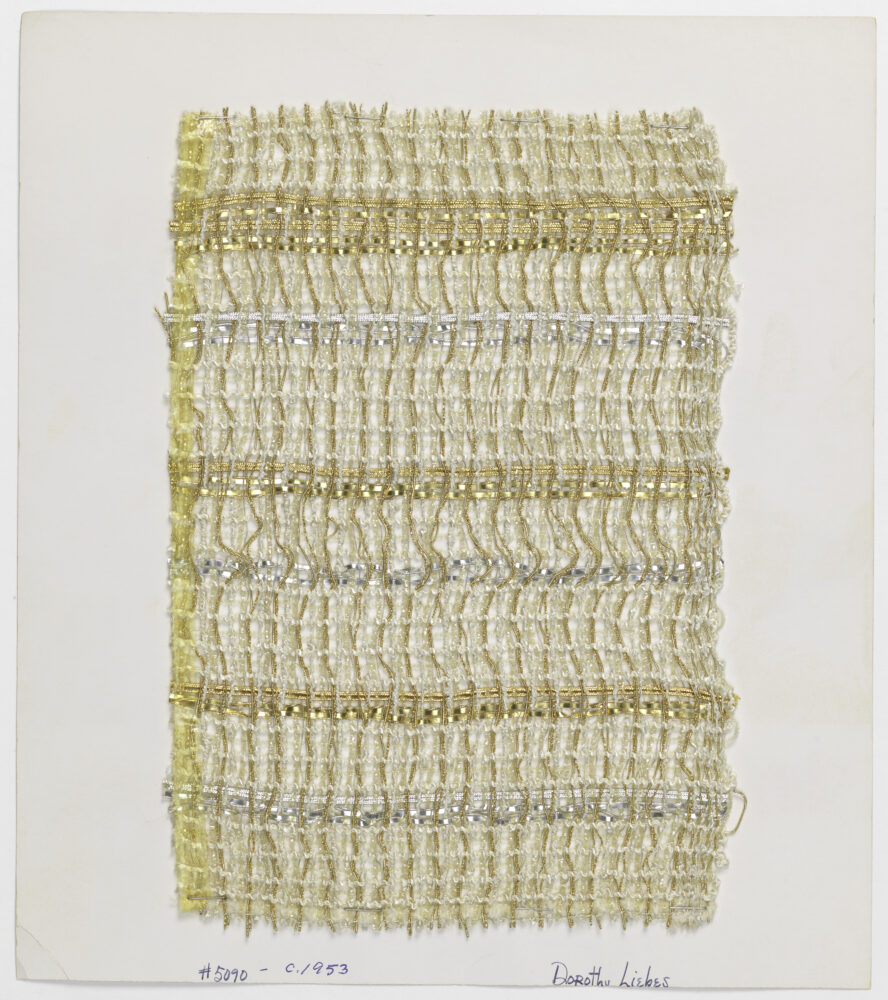

By contrast, her postwar consultancy with DuPont gave Liebes insider access to the greatest explosion of new textile fibers, dyes, and finishes in history. Her hands-on prototyping and ideation shaped the development of the new synthetic yarns, as she consistently pushed for improved “hand” and more varied surface qualities, which resulted in fibers with cross-sections designed to mimic the properties of cotton or linen, or air-textured yarns for a loftier, more wool-like character. She even added a Collins Twister—a piece of yarn-winding machinery—to her studio equipment to create her own spins and add variety and interest to too-uniform synthetic fibers. [2]

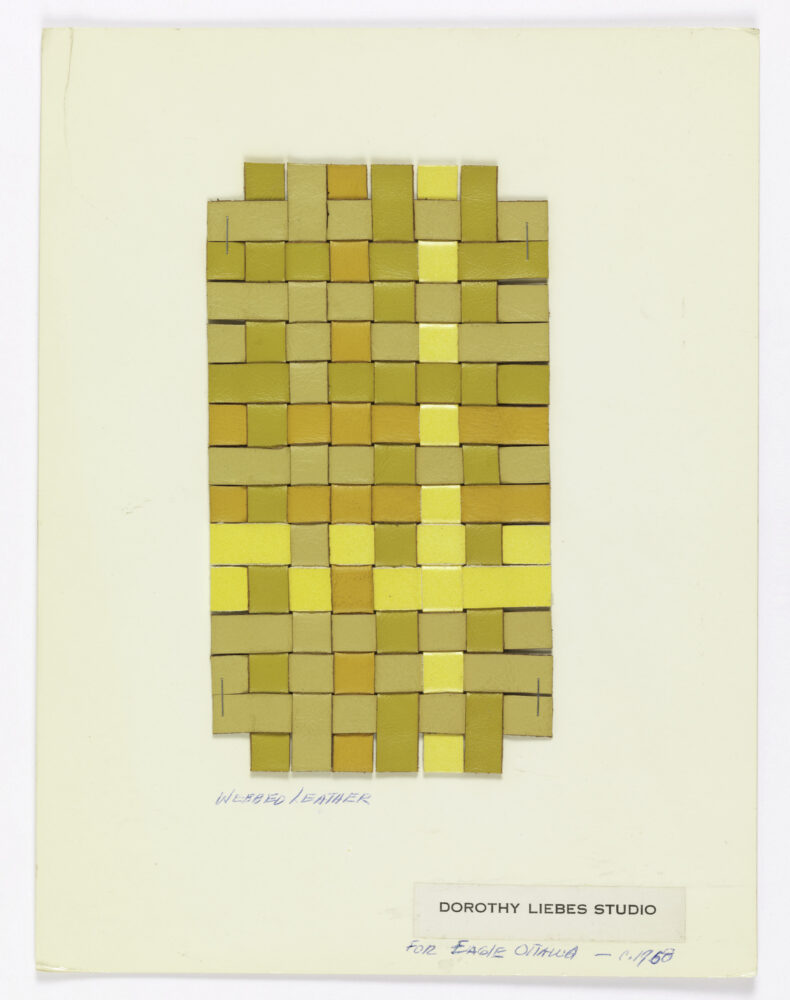

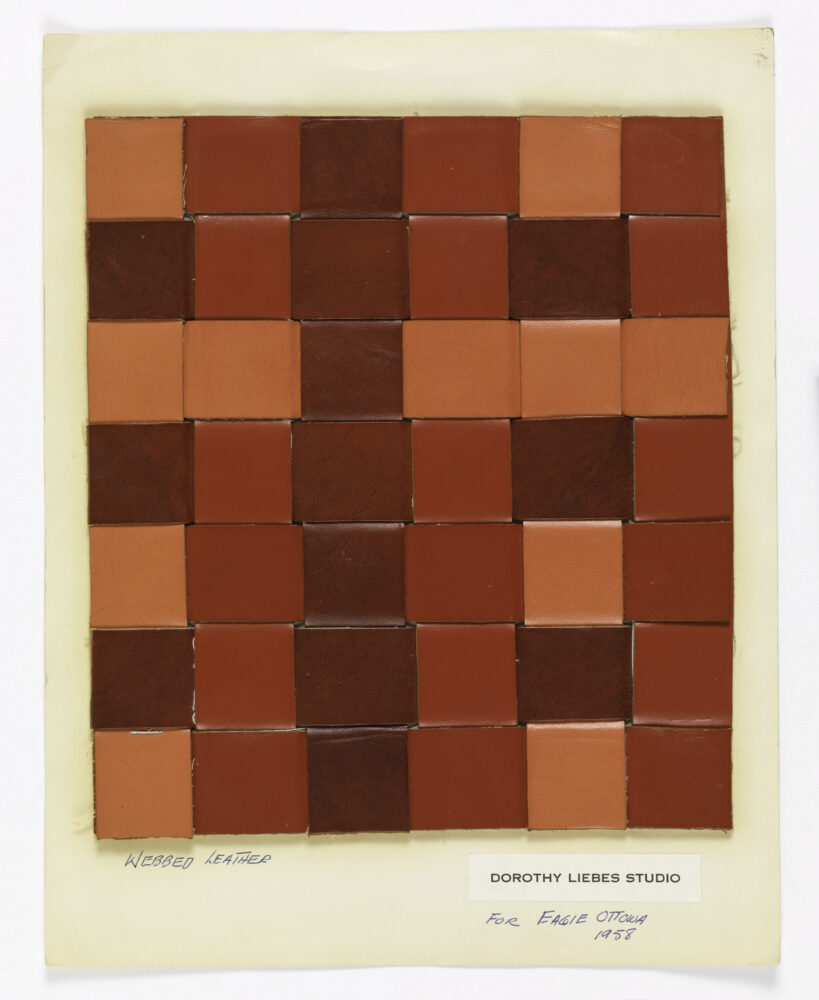

As an authority on design and weaving, Liebes was invited to lecture and run workshops around the globe. Whether addressing handweavers in Portland, Oregon, or textile manufacturers in Shizuoka, Japan, she advised scouting for unexpected sources and investigating local materials. “In every community there are materials more or less peculiar to it, and indigenous to the region, which make for unique woven fabrics.” [3] Her own local community was San Francisco’s Chinatown, which she scoured frequently for trimmings—ribbon, rickrack, ball fringe, and metallic gimp and soutache in every form—as well as the bamboo and other reeds she used for her woven blinds. “Once upon a time,” she wrote, “we were confined to just animal or vegetable materials—grasses, flax, cotton, wool, and, loveliest of all, silk. But we have learned that this is a great, wide, beautiful and resourceful world: we have also opened our eyes and imagination with new awareness. We can weave with unlimited materials—string, trimmings, braids, ribbons, oilcloth, cork, wood strips, reed, lace, paper, pine needles and leather. We can use all kinds of scraps, which is not only good citizenship in the conservations sense, but conducive to exciting and interesting textures.” [4]

NOTES

[1] Dorothy Liebes, autobiography (unpublished ms.), 87. Series 4, Box 4, Folder 10, Dorothy Liebes Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[2] Dorothy Liebes, letter to Herber Allen, January 30, 1959. Series 5, Box 6, Folder 41, Dorothy Liebes Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

[3] Dorothy Liebes, autobiography (unpublished ms.), 299.

[4] Dorothy Liebes, “Tomorrow’s Weaving,” Woman’s Day, April 1944, 32.